There was a time not too long ago when the “great American road trip” was the foundation for the everyman’s epic. Vehicles were more prominent, heavier, and not equipped with the technology that provides us with the gas economy, air conditioning, or navigational prowess that we have today.

A breakdown in a city could result in being stranded for weeks in a remote town as the only mechanic within three hundred miles figured out how to fix your car. Every exit didn’t have a gas station, there was no such thing as a coast-to-coast connection, and your playlist was limited to whatever cassette tapes you had on hand.

The American highway system was established in 1956 by President Eisenhower’s Federal-Aid Highway Act. It was a way to have a national network of roads to rapidly move troops and resources and to serve as a boon to the trucking and shipping industries.

Before the interstate system existed, American highways were primarily left up to the web of asphalt that states and counties laid out to suit their own needs. Those who drove cross-country on them required an atlas and the help of locals to make it from one point on the map to the next.

The roads were sometimes in rough shape, took blind corners, and were inherently more dangerous. The speed limit was significantly slower than what we might expect today.

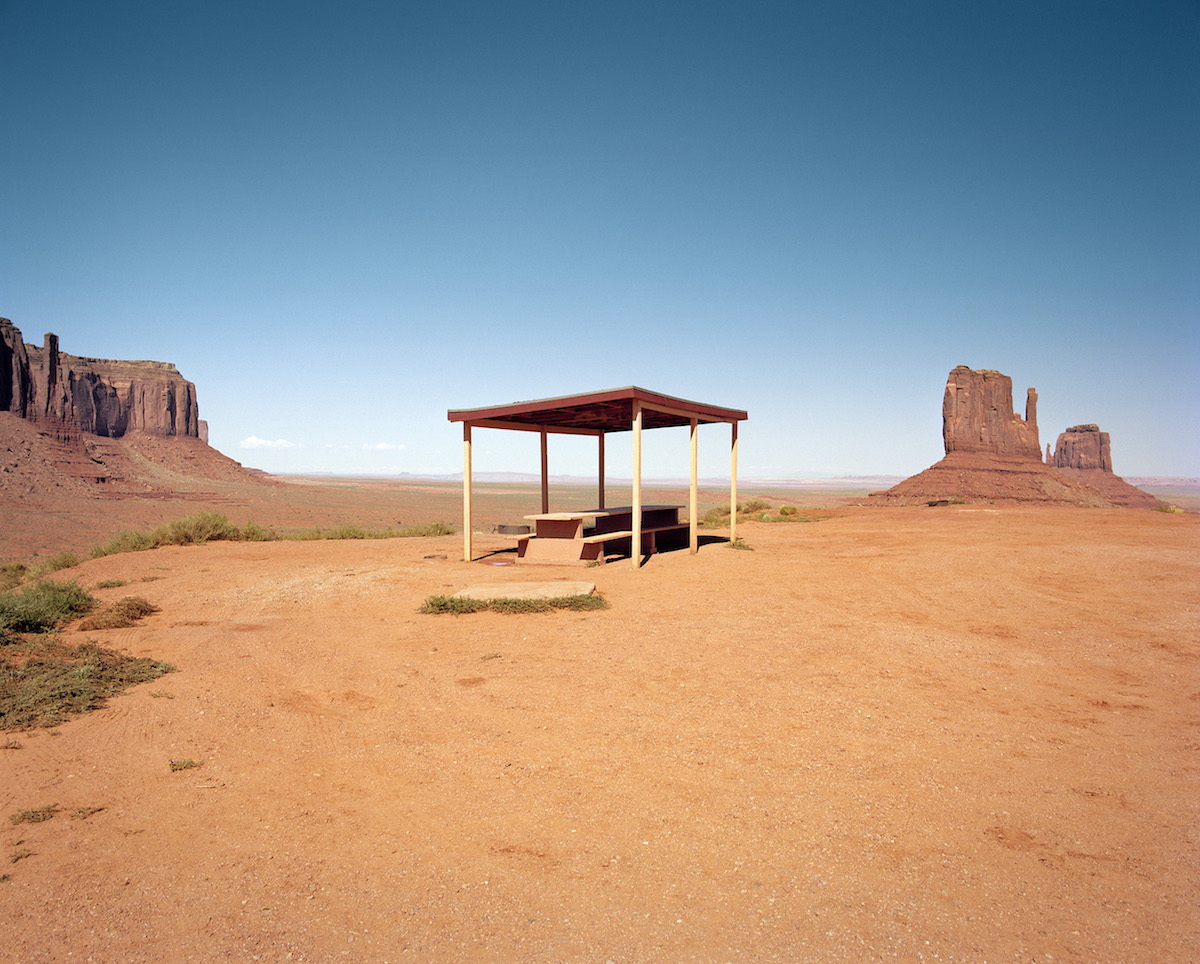

On these state roads, before long, you needed a rest stop—a place to pull over, stretch your legs, prepare a meal, and take in the scenery. A place, maintained by the local government, that served as a way to highlight the beauty passing by your windshield at 50 miles per hour. At its most simple, a few concrete slabs arranged to resemble tables or provide shelter from the rain.

Some rest stops feature structures that embody the essence of local art or architecture. One rest stop in Texas features permanent Indian-lodge style shelters made of steel. In South Dakota, wooden picnic structures overlook mountain ranges in the distance. Others in Nevada are squat, brick structures hidden at the foot of rust-red cliffs that soak up the shadows of a setting sun.

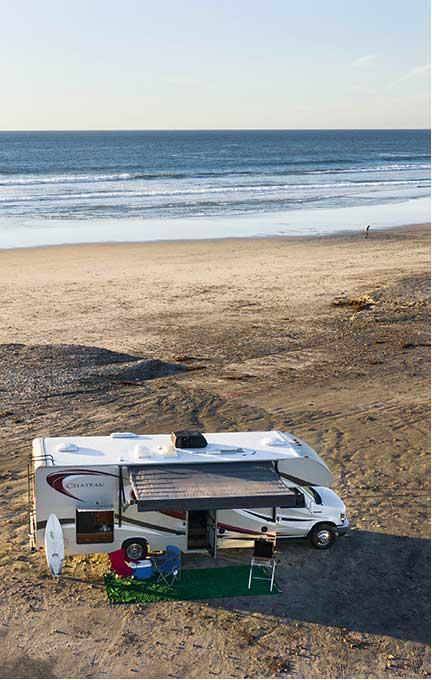

When it came to long-haul travel and road trips, the interstate took over. And why wouldn’t it? The interstate was, and still is, a well-maintained path that connects two distances, all in a relatively straight line at high speeds. You could travel from L.A. to Las Vegas in five hours, and Las Vegas to Denver in 12 hours. Trips where the only stop was for gas started to become the new normal.

Travel became about the destination, not the journey. As a result, rest stops on the side of state highways grew cold and outdated as brightly lit rest stops with gas and convenience foods popped up at every other interstate exit. The idea of a rest stop became a novelty.

In this change, what did we lose?

Photographer Ryann Ford attempts to capture an answer to this question in the pages of her coffee table book, The Last Stop. This extensive, well-curated photo book works to preserve the holdouts of the very thing that made the modern idea of manifest destiny possible: the rest stop.

Each photo highlights a rest stop somewhere across the West that has been left to decay, lost to time, or left abandoned on the side of a road not traveled anymore. At each stop lies an invitation to get out of the car, wander the landscape, and take in a gem of the region that might not be highlighted in the area’s welcome center.

Rest stops like the ones Ford showcases would be ideal at any number of interstate turnoffs. On Interstate 70 westbound on the Utah border are numerous signs encouraging tired drivers to pull over and get some shut-eye. These pull-offs are sandbars in full-sun on the side of the highway. The idea might be to keep the car running, the AC on, and hope the passing headlights don’t disturb your sleep.

Today, vehicles are installed with software to detect tired driving and the great American Southwest is considered in the American canon as vast expanses of nothing, punctuated by landmarks you might want to see—so why not drive through them as swiftly as possible?

We’ve lost the sensation of the journey; the idea of being somewhere that isn’t your home. The truck stop with the gas pumps and the fluorescent lighting where a dozen other families are also getting out of their vehicles looks just like the gas pump at home. The coolers inside have all of the same soda and tea, the same candy bars line the racks, and your credit card is as good here as it is at home. Every interstate exit is a sea of concrete and asphalt, and every sign is colored more or less the same.

Squint hard enough, and everything looks the same. And if everything looks the same, why leave in the first place?

Revive the rest stop. Next time you’re “just passing through,” make a point to pull over at these scenic locations.

Abiquiu ECHO Amphitheater: North on Highway 84 in Northern New Mexico, a pullout. An easy walk through a natural amphitheater, Abiquiu ECHO Amphitheater provides all of the echoes you and your children can bear to scream out.

Bonneville: Known as the flattest place on earth, the Bonneville Salt Flats in northwestern Utah have been host to notorious land-speed record attempts. It is worth a stop at the International Speedway to check out history’s fastest drives. The bleak harshness of the environment only shadows the impeccable beauty of the Salt Flats, and most descriptions of this location will barely do it justice.

Monahans Sandhill State Park: As the name suggests, this rest stop in Monahan’s, Texas is surrounded by significant dunes. The frequent desert winds have the locals stopping by every few days to clear the sand away from the roads and rest stop features surrounding the park.

Monument Valley: Monument Valley covers a vast expanse of a Native American reservation over the Arizona and Utah border. One of the most famous turnoffs and photo opportunities has been named ”Forrest Gump Point.” You may remember this vista from one of Gump’s cross-country runs. Today, it’s the highlight of many Instagram feeds. As you drive through, slow down a bit to prevent hitting anyone taking “that” photo.

Saguaro State Park: Southwest of Tuscon, Arizona is Saguaro State Park, home to some of the oldest Saguaro cacti in the world. Here, you can tour rock formations that feature ancient petroglyphs. Stopping at Signal Hill affords an expansive view of a landscape dotted with cacti.

Valley of Fire, New Mexico: Volcanoes are not just for islands and shorelines anymore. The Malpais Lava Flows nature area is a quick hike through an area that features delicate desert landscape that has grown out of what was once a volcanic landscape. Fret not though, the fissures that introduced lava to the area have long since cooled and hardened, leaving behind glassy, black igneous rock.